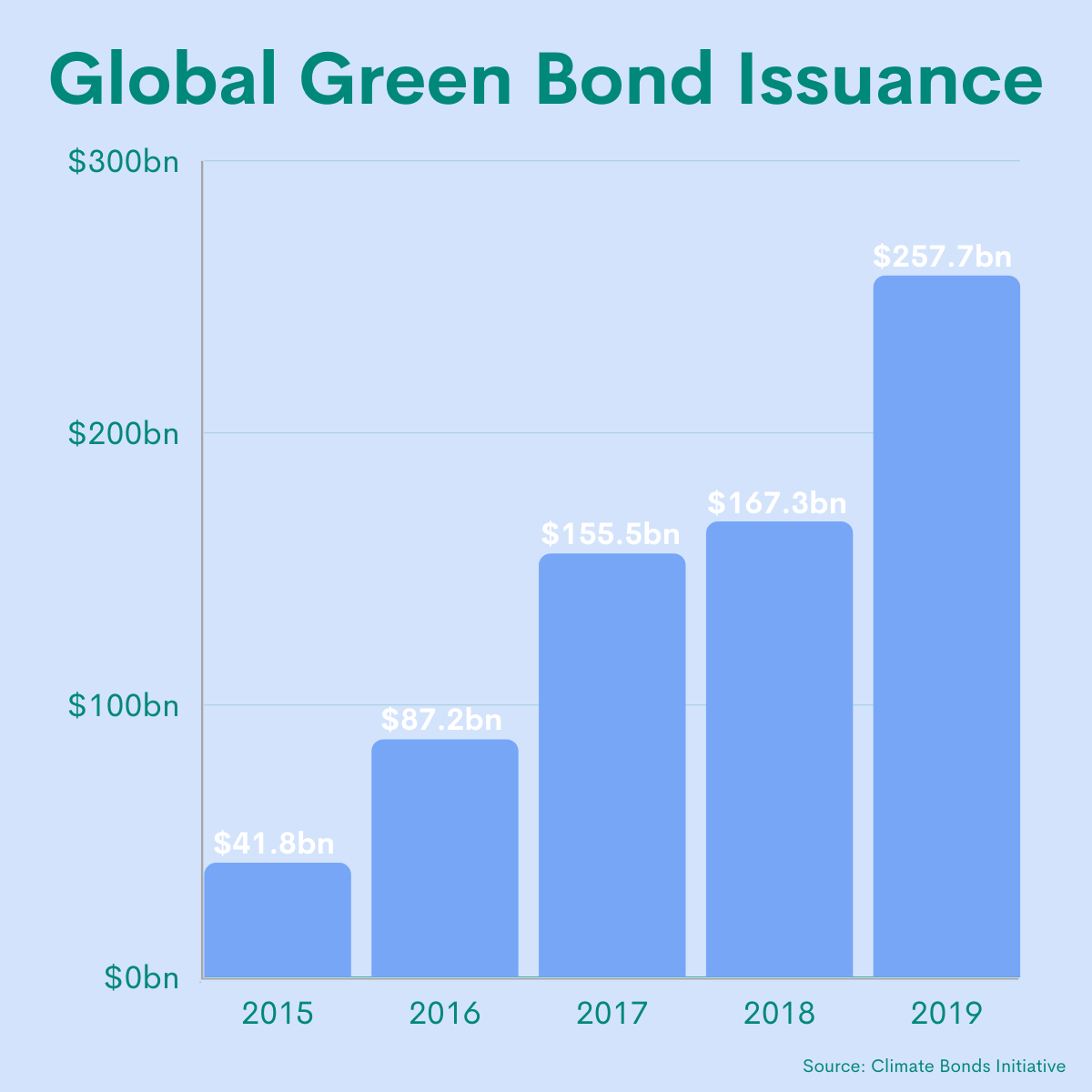

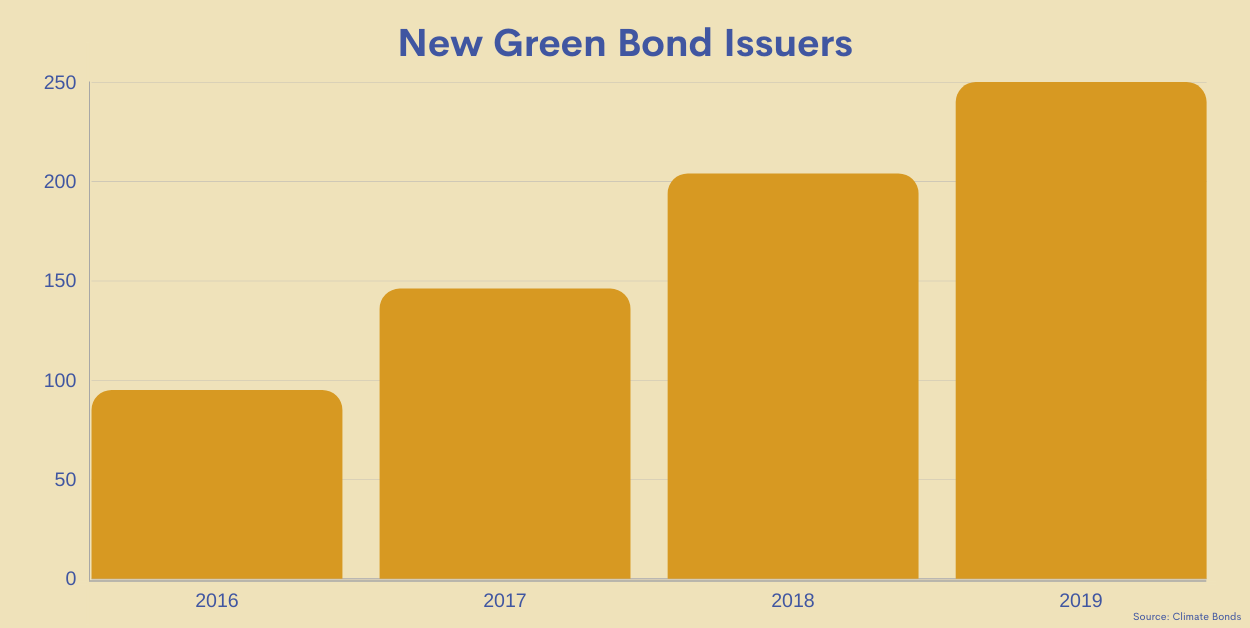

There’s no escaping the growth of green finance. Every quarter charts new records for issuance of green bonds or investment in funds that describe themselves as sustainable or that follow an investment policy guided by considerations of environmental, social responsibility and governance.

Meanwhile institutional investors around the world are using their weight as providers of corporate financing to push companies toward greater respect for the environment and the welfare of employees in their own operations and in supply chains and, increasingly, to commit to reduce carbon emissions in measurable ways or set a date to achieve net zero status.

This trend is now a fact of life in the financial industry, not least because of the role of institutions in pressing companies and financial service providers to embrace environmental and other sustainability goals, as well as the determination of the EU to implement legislation to increase public accountability.

Here’s a telling data point: the proportion of global investors that apply ESG criteria to at least a quarter of their total investments has risen from 48% in 2017 to 75% last year, according to Deloitte.

Open questions about the ‘green’ in green finance

Yet, the significance of this green finance trend in changing corporate and financial behaviour is less easy to measure.

In fact, the size of the market and its different segments is open to wildly different estimates, both in terms of current levels and projections into the future.

And just how green or how sustainable some, or even most, of these investments or assets really are is an even more ‘known unknown’.

The problem is the absence of standardised, universally accepted definitions and rules setting out what constitutes sustainable or ESG investments, assets and projects — and similarly standardised mechanisms to measure compliance.

The EU’s Taxonomy Regulation, which seeks to define sustainable activities, should help to fill the gap, although it won’t be applicable until the beginning of 2022.

That’s why arguably ‘greenwashing’ — promoters awarding financial assets and products an environment-friendly or sustainable label they don’t warrant — is a lesser problem than the simple inability to determine what green (or sustainable) actually means.

The green bond market, which currently totals around €660 billion in outstanding debt, is forecast to rise to €1 trillion by the end of next year and €2 trillion two years later, according to the Netherlands’ NN Investment Partners.

However, it warns that only 85% of green bonds deserve the label; the rest are issued by companies that may be undertaking environment-friendly projects but whose practices in other areas breach environmental standards.

Varying definitions of green finance

Take the investment funds numbers, for example.

Data provider Morningstar says European sustainable fund assets passed the milestone of $1 trillion during the third quarter, and global assets reached $1.26 trillion, while a record 166 new products were launched worldwide over the three months to the end of September, taking the total to 3,774 worldwide.

By contrast, the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance last year estimated that “some kind of environmental, social or governance analysis [in] investment decisions is now a factor” in $31 trillion of assets under management,

Meanwhile Optimas, a Boston-based capital markets consultancy, says the value of “global assets applying environmental, social and governance data to drive investment decisions” has almost doubled over four years, to $40.5 trillion this year. (By way of comparison, Boston Consulting Group estimates that the global asset management industry oversaw $89 trillion at the end of 2019.)

These numbers could conceivably all be correct, but it begs the question of what investments these very different totals include, how they are calculated, what constitutes the applicable sustainability or ESG principles, and how compliance with them is measured.

Misleading marketing

Some of the problems with the credibility of sustainable products are relatively easy to spot and have caught out major players like Fidelity Investments and State Street Global Advisors.

More broadly, the 2 Degrees Investing Initiative, a non-profit think-tank, has claimed that 85% of all “green-themed funds” have misleading marketing materials.

Together with the UN Principles for Responsible Investment network, the French-headquartered organisation has drawn up the Paris Agreement Capital Transition Assessment (PACTA), an online tool to measure the alignment of equity and fixed income portfolios with climate change scenarios. It says PACTA is used by more than 1,500 financial institutions worldwide, as well as by supervisors and central banks to assess the entities they oversee.

But it’s far from the only system in play and the credentials of providers aren’t always clear, notes Alessandro d’Eri, a senior policy officer at the European Securities and Markets Authority. “We have seen a boom in the number of..ESG rating and scoring providers, a largely unregulated area,” he says. “It is difficult for us to make sense of the scoring and rating if there is no clarity on the underlying methodology.”

Asset managers increasingly complain that some companies issuing green bonds are financing environment-friendly activities at the same time they’re involved or implicated in businesses whose impact is the contrary — like state-owned monopoly Saudi Electricity Company, which raised €1.3 billion from a green bond in September to install smart meters across its grid.

Constructive engagement

The Australian state of Queensland has issued bonds for initiatives including preserving the Great Barrier Reef, which is under threat from the impact of global warming, at the same time that it continues to promote expansion of its coal industry.

Others, like car manufacturers, are dressing up as green initiatives investment in production facilities for electric vehicles that they would be carrying out anyway. Still others are using green bonds to refinance investments they have already made.

Some equity investors in polluting companies or high carbon-emission industries justify their state on the grounds that it gives them the opportunity to engage with the businesses and encourage them to change their practices.

Maybe. But this, too, risks delivering an outcome that challenges quantification.

There’s no shortage of initiatives underway today to measure environmental and other sustainability factors to assist investment decision-making. The EU sustainable finance framework, which is well advanced, will progressively extend transparency requirements throughout the European financial industry, which could create the foundation for a standardised global rulebook.

Until then, though, when it comes to green finance, determining what is sustainable and what is not, what’s real and what’s greenwashing, is likely to remain as much art as science.

If you’re interested in sustainability, sustainable finance, and the funds sector, you should read: