This article is from VitalBriefing’s Sustainability Matters content series, in which we speak with experts across every facet of sustainability, ESG, sustainable finance, impact investing and more. If you or a colleague are interested in participating in the series, please get in touch by emailing eschrieberg@vitalbriefing.com.

Impact investing has drawn increasing attention from investors and advisors in recent years. However, financial experts argue that many investors with the ‘right’ intentions fail truly to understand what investing for impact actually means – and that lack of insight is restraining the sector from reaching its potential.

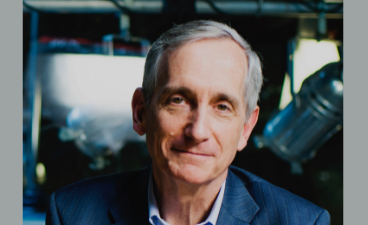

Alexis Figeac, an impact investing expert who, with his colleagues at Sustainability Investors, is in the process of establishing a €150 million venture fund to invest in environmental businesses, discusses issues including the importance of intentionality in impact investing.

Has the impact investing sector grown in line with its profile, which has risen sharply in recent years? What’s driving this surge in interest?

The sector has grown tremendously. The Global Impact Investing Network estimates that over 1,700 organisations with around $700 billion in assets under management now invest for impact.

There is of course a wide spectrum of strategies that fall under the ‘impact investing’ umbrella, from KKR’s $1.3 billion Global Impact fund, which makes private equity investments in environment- and education-oriented businesses, to smaller funds that focus on developing countries, such as Finance-in-Motion or social enterprises like BonVenture.

The depth and nature of a specific strategy’s impact can therefore vary. To me, this is an important sticking point, because however much the sector may have grown, so much more capital could be channelled toward impact investing.

Some may argue that all impact is good impact, but I feel this is too unqualified of a statement. It’s important to note that the current surge in interest, which far outweighs any corresponding surge in action, has more to do with the intent to do something positive with one’s capital – and especially to effect real-world change.

This means that although greater volumes of capital may be available to invest in traditional impact areas such as microfinance and clean energy in developing countries, it’s the business models closer to home – around the local, sharing or circular economy – that have become more popular.

Looking more closely at this trend, the subject of sustainable food in particular brings together social, environmental and economic concerns. Procuring local food, paying better prices to smaller farmers, making organic agriculture economic and available to a wider community, and avoiding ‘food miles’ certainly create a range of positive impacts. Moreover, saving food from expiry and avoiding food waste in general also deliver environmental and social benefits. Examples of businesses focused on these areas in France and Germany include La-Ruche-qui-dit-Oui!, Stadtfarm, Phenix and Foodloop.

Aside from food and agriculture, impact investing is also creating financing opportunities for non-conventional housing initiatives, such as multi-generational, co-operative and community housing.

For example, after years of wrangling with traditional real estate lenders, it was €130 million in financing from ethical institution GLS Bank and other German lenders that enabled the Möckernkiez Housing Cooperative to fulfil its ambition of developing a community of 471 units in Berlin’s Kreuzberg, combining social and private apartments purpose-built to meet passive housing energy standards.

Is impact investment overshadowed by the current focus on efforts to curb climate change or can it be part of it?

I believe it can certainly be a part of it. One could argue that a substantial segment of climate change mitigation is even appealing to investors focused on financial returns.

In many parts of the world, the Levelised Cost of Energy – the total lifecycle cost of a facility compared with the amount of energy it is expected to produce – that comes from renewables is competitive with fossil-based sources.

Indeed, in many cases after factoring in variables such as the geopolitical risks associated with the supply of fossil fuel energy, the progress of energy storage availability, future carbon pricing and Power Purchase Agreements or other pricing certainties, investment in renewable energy by institutional investors offers risk-adjusted returns for power-producing assets.

Therefore, not only should a global energy transition financed by asset owners and banks be possible, it can be based on an underlying asset that is quite straightforward. This is why there isn’t necessarily competition for the same pockets when it comes to capital for social impact.

Times are certainly changing. For instance, financing a European wind farm a couple decades ago might have been considered risk capital. It would have been seen by many as an impact investment facing factors such as project risk and concern about the experience curve. Nevertheless, investors understood it was impactful by reducing CO2 and paving the way for dissemination of the technology. I should know, having invested in three wind farms in the 1990s that have yielded varying fortunes.

Investing in similar projects today in Europe no longer catalyses change in the way impact investors usually intend.

Financing renewable energy in a developing country is a totally different matter, especially off-grid, as it profoundly improves the lives of the local communities. Providing lighting, refrigeration and telecommunications to off-grid communities enables better health care, education and economic opportunities – in addition to displacing diesel generators for power and kerosene lamps for lighting.

Such investments therefore serve social, environmental and economic purposes: true impact investment.

The reason I’ve given such a ‘macro view’ answer is that with this topic, as with so many aspects of impact investment, it’s a question of intentionality – what does the investor seek to achieve:

- Deployment at scale of renewable energy to help mitigate climate change while still offering market financial returns?

- Or deploying renewables at a smaller scale but with a greater social impact and a diminished return given the country and project risk – where there are few to no guarantees?

In truth there is a wide range of potential impact projects that would complement large-scale climate change mitigation goals.

One example would be promoting biodiversity while simultaneously enabling income generation. Another is targeting the impact areas I mentioned earlier, such as food and housing, that relate to community needs and require smaller, tailored initiatives rather than massive capital deployment in the energy sector.

The blind-spot that huge investments in renewable energy and decarbonised transport struggle with is that although such projects will have a medium-term result in slowing the devastating impact of climate change on vulnerable communities, they do not actually address the immediate needs of those at the bottom of the pyramid.

These stakeholders’ most pressing needs relate to issues such as sanitation, education, gender equality, eroded soils and coastlines, commoditised agriculture, raw material extraction, and access to clean energy.

Although overseas aid is deployed in these areas, impact investment can have a greater catalytic effect, empowering local actors both economically and socially, and circumnavigating administrative bureaucracy.

What are the key motivations driving impact investment? Are impact investors predominantly institutions or individuals?

It ultimately comes down to each investor’s priorities. Of course, all impact investors wish their investment to support solutions to social or environmental issues, and to benefit a range of stakeholders.

However, impact investment is not philanthropy, and therefore inherently seeks a return – i.e. the underlying asset or project is usually long-term in focus and relatively illiquid.

Some impact investors may be prepared to accept below-market financial returns as long as those results are balanced by the social or environmental benefit.

Going even further, in the context of rock-bottom central bank interest rates, some foundations are happy simply with capital preservation as long as the impact is delivered. Some of this capital may also be integrated into blended finance.

As to the actors behind impact investment, we must accept that it is hard to ask pension fund managers and insurers to accept lower returns when they have to achieve an equitable balance between different generations of contributors. Thus, it is foundation and family money we tend to see in impact investment.

Toniic, for example, is a group of wealthy private investors that dedicate 100% of their invested capital to meet impact criteria.

Public institutions are also often involved in impact investment; Sitra, the Finnish Innovation Fund, has been pioneering in establishing and launching social impact bonds.

Ultimately, what distinguishes impact investors are two salient features: intentionality and additionality. While I have already discussed intentionality, additionality should be understood as the catalytic role that impact investment can actually play.

In other words, the impact investor asks the question: “What impact would have occurred had I not invested?” The answer – the difference between with and without the investment – determines the additionality.

Sometimes it is marginal, such as where other sources of capital are available on similar terms. But there are cases where the additionality could be huge, because the impact might never occur without that investment.

Is greenwashing a particular problem in impact investment? What indicators exist to measure the social (or environmental) impact of a project?

Greenwashing is a problem for the finance industry in general. Frankly, it’s an issue across the business world.

One must distinguish public equity investment from investment in private socially- or environmentally-oriented businesses or projects. While there may be scope for moving millions into ESG-compliant stocks, the difference lies in the fact that the underlying businesses do not change their mission.

Hence, I see this as less of an issue in impact investing. Indeed, as I mentioned earlier, salient features of impact investing are intentionality and additionality.

Whereas ESG is a by-product of many large enterprises’ normal business, social or environmental impact is the raison d’être of a team or project involved in impact investment finance. Many traditional businesses struggle with ESG reporting because it is not core to their mission.

While it may not be inherently tied to impact investing, greenwashing must be considered. In impact investment it is as much an issue of inaccurate representation as it is one of the reporting metrics that currently exist. Therefore, to combat greenwashing, measurement of outcomes, including the use of appropriate indicators, is vital.

For starters, on the environmental side, impact measurement needs to go beyond mere carbon and water reporting metrics.

Although greenhouse gas emissions reporting has become mandatory for large corporates, impact-oriented businesses (regardless of size) often offer solutions to mitigate GHG for their clients and for society as a whole. Such scope 3 measurement and reporting, however, represents a whole raft of challenges.

Smaller impact initiatives are better catered for through methodologies such as IRIS+ and IMP, which combine measurement of both an organisation’s own footprint and external outcomes.

Concerns around greenwashing may be allayed through a holistic approach. Indeed, impact investors ultimately must take a holistic view of what is being achieved by their project, especially when technology is involved. It’s imperative to understand the ecological footprint innately tied to that technology. From that point of view, Life-Cycle-Assessment is a good, if purely environmentally-focused, tool.

I also am a fan of IMP’s approach, which takes five dimensions to also blend in the social dimension in order to achieve a more holistic view without neglecting risk.

For those who are interested, I would highly recommend reading the excellent overview recently published by the European Venture Philanthropy Association, “Navigating Impact Measurement and Monitoring”.

How should impact investing fit with other sustainability approaches?

As an impact investor, I could go on forever answering this question. Suffice it to say that the UN has set out 17 Sustainable Development Goals and impact investment can play a role in many of them.

Fulfilling several of them simultaneously is even achievable through impact investment. One example that comes to mind is the Delhi-based social enterprise “Women on Wheels,” through which female taxi drivers at the wheel of zero-emission vehicles specifically and exclusively serve female clients.

Given the ecological and social boundaries of our world, impact investment – and the way it represents purpose of capital – is a beacon that lights the way for a sustainable planet. Or, as Professor Kate Raworth states, it can help finance “a safe space for humanity.”

— — — — —

We would like to thank Young-Jin CHOI for his help reviewing this article prior to publication.

Do you need to stay on top of ESG and sustainable finance news? Check out the Sustainable Finance News & Insights Briefing, bringing you news summaries and market analysis on regulation, legislation, investment trends, products and more.

Produced by expert financial journalists, it cuts through the confusion, saving you time by delivering everything you need to know in one monthly newsletter.

Alexis Figeac is an early-stage investor and board member for many green technology firms. The founder of Axiom VC, an early German cleantech VC fund, and ex-partner at the €100 Million Entrepreneurs Fund in London, he also led Sustainable Business and Entrepreneurship at the UNEP Collaborating Centre on Sustainable Consumption and Production. Currently, he and colleagues at Sustainability Investors LLP are setting up a €150 million venture fund to invest in decarbonised- and circular economy-oriented businesses.