This article is from VitalBriefing’s Sustainability Matters content series, in which we speak with experts across every facet of sustainability, ESG, sustainable finance, impact investing and more. If you or a colleague are interested in participating in the series, please get in touch by emailing eschrieberg@vitalbriefing.com.

Sustainable finance appears to be at a crossroads, caught between surging investor demand and gradually tightening regulatory requirements on one side, but struggling on the other with a plethora of inconsistent standards and measures and an acute shortage of data. One way to look at this is to assume that greenwashing is rife – but another is to view the current situation as a way-station on the road toward a genuinely sustainable economy.

As the imperatives of climate change and growing inequality become ever more urgent, and sensitivity to both issues are heightened by two years of Covid-19, sustainable, green or ESG investment and assets are steadily taking the financial industry by storm.

The sector remains awash in an alphabet soup of sometimes interchangeable or ill-defined expressions and acronyms, including sustainable finance, ESG, impact investing, ethical investment, corporate social responsibility, green bonds, SASB, TCFD and SFDR. It’s a daunting learning curve for private investors as well as asset managers and corporate securities issuers.

But the need to understand and clarify this new landscape has become still more pressing.

Enter the EU taxonomy

Serious efforts to define and prescribe what activities do or do not belong in a green or sustainable investment framework are becoming progressively embedded in law. The most conspicuous example is the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Package and its most headline-grabbing components, the Taxonomy Regulation and Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation. Both are already in force, although some detailed provisions will not apply until early 2023.

Financial market participants subject to the SFDR include investment firms, pension funds, asset managers, insurance companies, banks, credit institutions that offer portfolio management and financial advisors. Companies with fewer than 500 employees are not obliged to follow the rules. But if they don’t, they must explain why not.

The EU taxonomy – billed by the European Commission as “a common classification of economic activities significantly contributing to environmental objectives, using science-based criteria” – underpins the SFDR by informing their classification, or not, of activities constituting sustainable investment.

At present, the most important application is in determining whether investment funds should be classified either under the regulation’s article 8 as financial products with environmental or social impact characteristics, article 9 as possessing sustainable investment objectives, or article 6 (neither).

Laboured birth

These legal developments have proved complex to implement, leading to delays and complaints from financial institutions, which complain that the information they will be expected to provide, notable sustainability reports by companies, in many cases do not yet exist.

Indeed, in many cases, they will not do so until the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, which is also based on the EU taxonomy and will vastly extend companies’ reporting requirements, comes into force; it is currently wending its way through the union’s convoluted legislative process.

In the spring, France’s EU Council presidency will begin negotiations on the draft with representatives of the European Parliament. Currently, companies are still scheduled to publish their first reports in the first quarter of 2024, covering the previous year. But the timetable is highly ambitious and could well slip, depending on how long the legislation takes to be finalised and win approval.

Reflecting the difficulties of asset managers and other investors in gathering data from their portfolio companies, compliance with the SFDR in 2022 amounts to following high-level principles. However, from next year, institutions will be obliged – to the extent that’s possible – to follow much more detailed so-called ‘level 2’ prescriptions.

The adoption of the EU taxonomy has also been disrupted by an essentially politico-economic dispute about whether the use of natural gas and nuclear power should be classified as sustainable energy sources.

To environmentalists’ rage, the European Commission has proposed doing so, subject to certain conditions. This could be overturned by the European Parliament, although such a decision might further delay the full application of the taxonomy as a whole. In any case, organisations seeking to define policies on sustainability are free to make their own judgement as to whether nuclear and gas should be treated as such.

Is sustainability more profitable?

A range of different metrics can be used to score the performance of a company or an ESG fund in each of these areas. Specialised rating agencies have sprung up to fill the gap, although there is no guarantee of consistency among them; for now such providers are unregulated, although there are moves to change that. In the meantime, the assessments they provide should be seen more as pointers than absolute judgements.

Investors usually will weigh up sustainability factors alongside financial performance; whatever their commitment to ESG principles, many institutions, especially pension funds and insurance companies, are legally obliged to seek returns that provide beneficiaries with an adequate retirement income or cover future policy liabilities.

These aims may not be in conflict. Many analysts argue that companies indifferent to ESG factors are liable to underperform over time due to their greater exposure to environmental, legal and reputational risks.

The extent to which sustainable investments already outperform or at least match conventional investments is a matter of lively academic and industry debate. An analysis by data provider Morningstar in 2020 found that sustainable funds outperformed their traditional peers over multiple time horizons, with average five-year returns for Global Large Cap Blend Equity strategies of 7.3% for sustainable funds and 6.1% for traditional vehicles.

More recent studies have found similar results.

However, critics say the impressive performance of sustainable funds is artificially boosted by the inclusion of technology stocks, whose impact on climate change is complicated – think teleworking and automation, but also server farms, with their colossal energy and cooling needs. In addition, funds badged as ESG or sustainable might contain a minority of investments that do not meet the advertised criteria (and could deliver an outsized proportion of its returns).

Socially responsible and impact investing

Other ways of approaching sustainable investment are gaining ground. Investors – institutions and individuals, but also high net worth individuals and family wealth entities – are increasingly looking beyond climate impact to broader elements of impact on society. Socially responsible investing (SRI), which has been around for at least a couple of decades, entails a screening process that prioritises certain companies or industries – and more often eliminates others – for a fund or investment portfolio.

So-called adverse screening may cover entire sectors, such as weapons, gambling, tobacco, pornography or fossil fuels, or relate to the reputation of individual companies, which might be affected by cases of mistreatment of employees, use of child labour or environmental damage. SRI decisions may reflect personal values, including political and religious factors.

Impact investing is increasingly entering the mainstream and such strategies underpin many of the funds classified as having a sustainability purpose under the SFDR’s article 9. Says Denise Voss, chairwoman of Luxembourg’s fund labelling agency LuxFLAG, a pioneer in the assessment of sustainability claims: “Impact investing… [chooses] companies that are actively seeking to make tangible improvements, for instance in the quality of drinking water for communities. Investors usually expect a profit from such a company, but its impact will be as important or even more so for the impact investor.”

That variation in importance is reflected in two key impact investing terms – ‘concessionary’ and ‘non-concessionary.’ The former means that achieving returns is of secondary or minimal real importance, and is typically the preserve of foundations or high net worth individuals. By contrast, ‘non-concessionary’ means that investors still expect a fair return.

From green to sustainability-linked bonds

Meanwhile, government and corporate bond issuance has become a central pillar of the market in sustainability assets. Pioneered a decade and a half ago, green bonds are now a staple of global securities markets, often commanding higher prices (and thus delivering lower yields) than conventional debt. They are frequently used to raise money for purposes such as financing or refinancing a specific project or activity such as renewable energy generation, home energy efficiency or pollution and emission-free transport.

There is concern in this sector, too, that blanket assertions of bond proceeds being used to benefit the climate, the broader environment or social goals may not be backed by concrete, measurable results.

One answer is sustainability-linked bonds or loans, for which the interest rate is tied to meeting specific targets in areas such as greenhouse gas emissions, wastewater discharge or energy consumption, giving issuers a financial incentive to keep their ESG promises.

However, with the growth of sustainable or ESG investment has come the spectre of greenwashing – where companies or organisations invent or exaggerate their green credentials to attract funding on favourable terms.

But the number of issuers outright falsifying their sustainability attributes is probably greatly outweighed by those whose ESG characteristics are hard, even for themselves, to evaluate. Do energy-saving measures by fossil fuel producers count? How much of a housing development needs to be made available to low earners for it to qualify as having a social impact?

In search of uniform standards

Investors must grapple with the lack of a universally-accepted standard ESG reporting framework for companies. George Serafeim of Harvard Business School and Sakis Kotsantonis of UK sustainable investment consultancy KKS Advisors point to the variety and inconsistency of data and measures and how companies report them.

For example, they say that with more than 20 different ways for companies to report employee health and safety data, inconsistencies lead to significantly different results for the same group of companies.

At the moment, decisions on many of these questions is more art than science. But there are reasons to believe this will change. One is the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, which will set out detailed transparency requirements for as many as 50,000 companies across Europe.

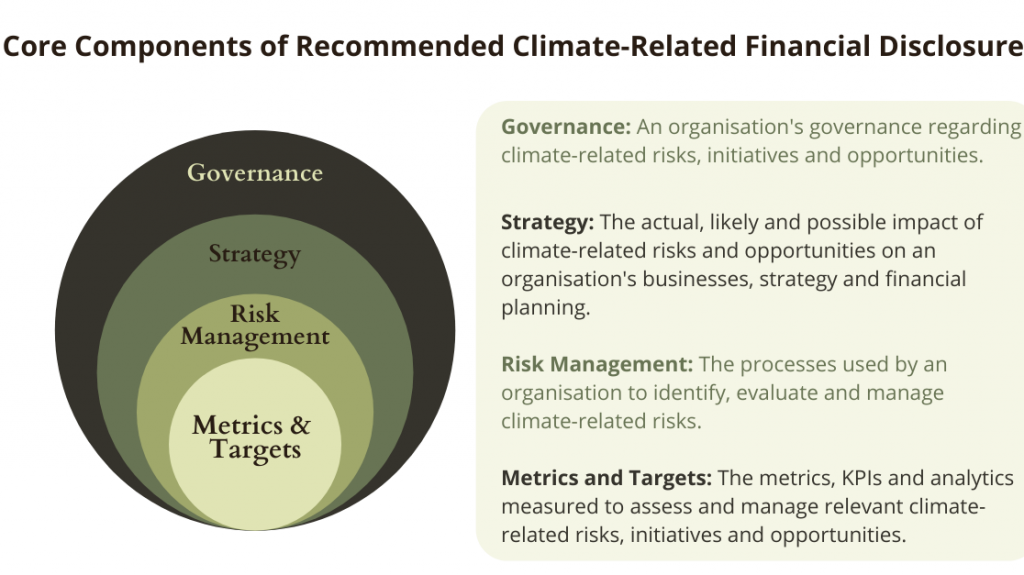

Already assessment frameworks are becoming harmonised by initiatives such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) for sustainability performance disclosures and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) for reporting on climate risk.

BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, now expects the companies in which it invests to use both the SASB and TCFD standards. European experts believe the enforcement of regulatory technical standards to bring detail and teeth to the SFDR from next year will oblige asset managers to provide in-depth data to justify, for example, their description of funds as possessing sustainability characteristics under article 8 of the legislation.

Already, Morningstar has removed 1,200 funds self-described as green, ESG or sustainable with assets totalling $1.4 trillion from its European sustainable universe list after assessing documentation about their investment processes. Next year, the more intensive reporting obligation could mean that in some cases article 8 labels might have to be, embarrassingly, withdrawn.

But probably rather more fund firms are now working flat-out to ensure their products meet the increasingly demanding standards.

Do you need to stay on top of ESG and sustainable finance news? Check out the Sustainable Finance News & Insights Briefing, bringing you news summaries and market analysis on regulation, legislation, investment trends, products and more.

Produced by expert financial journalists, it cuts through the confusion, saving you time by delivering everything you need to know in one monthly newsletter.