Luxembourg Stock Exchange keeps a close eye on the Global Green Finance Index (GGFI) — a six-monthly evaluation of “the depth and quality of 78 financial centres … [that] serves as a … measure of the development of green finance for policy and investment decision-makers” — conducted by London-based research and consultancy firm Z/Yen.

As a jurisdiction with well-publicised ambitions to become a hub for sustainable finance, built around the Luxembourg exchange’s pioneering role as a listing venue for green bonds, and Europe’s largest investment fund domicile, the grand duchy gives considerable weight to the listing — the seventh of which was released in April with some unpleasant news: Ranked fourth in the world last autumn, Luxembourg has slipped back to sixth of 78, overtaken by Oslo and San Francisco.

It’s a disappointment at a time when European legislation including the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation and the EU’s green taxonomy rules are bringing green finance closer than ever to the industry mainstream.

Narrow margins

Z/Yen notes that its scoring system, a mix of statistical measures and qualitative assessments from industry members and others, is tight and margins are narrowing. It says the spread of ratings among the top 10 centres in the index is 29 out of 1,000 compared with 51 for the previous edition.

Luxembourg received seven points fewer out of 1,000 in April; San Francisco (+3) was the only centre in the top nine to improve its score.

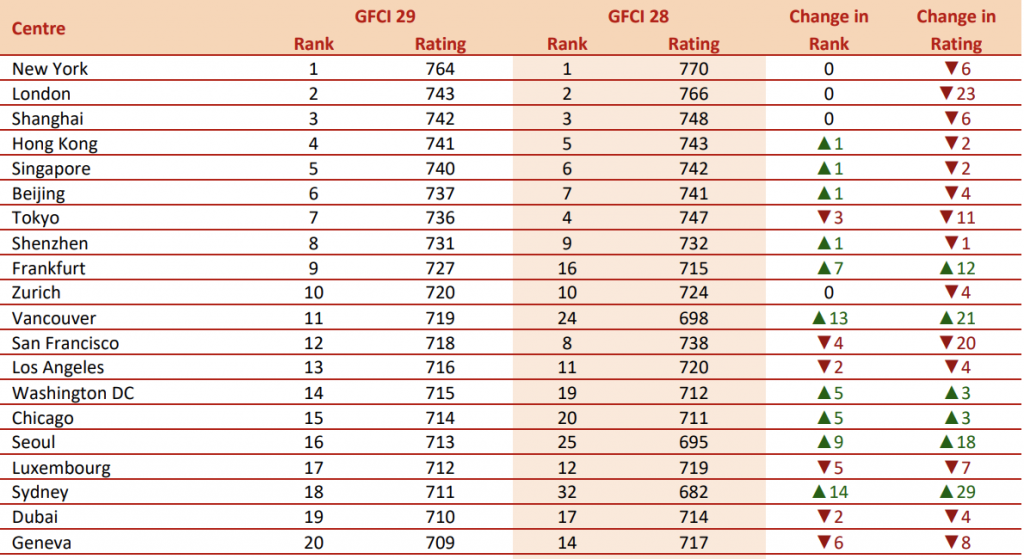

Still, there’s a pattern here. In March, Luxemburg slid seven points (again out of 1,000) and five places to 17th out of 114 in the Global Financial Centres Index (GFCI), which was launched by Z/Yen in 2007 and is now in its 29th edition.

No longer can the grand duchy boast of being the eurozone’s highest-rated financial centre, after being passed by Frankfurt (up seven places to ninth).

Since the reports do not offer detailed analysis of the performance of each financial centre apart from the highest ranked, it’s not easy to deduce why Luxembourg has dropped over six months.

One possible reason might be the country’s longstanding and well-flagged difficulty in attracting employees with the specialist skills required by the financial industry and its green finance players. But it’s not evident that Luxembourg’s capacities as a financial hub have deteriorated significantly over so short a period.

Quantitative and qualitative data

Still, there are reasons to be cautious about accepting without question the scientific basis of the Z/Yen indices. How are the rankings made? The Green Finance index was compiled using 140 “instrumental factors” – quantitative measures from independent providers such as the World Bank, Economist Intelligence Unit, OECD and United Nations. The Financial Centres index calculation involves 143 factors.

But this data is combined with assessments of financial centres provided by respondents to an online questionnaire – for the GGFI, 4,536 assessments from 739 industry members while for the GFCI, 65,507 assessments from 10,774 respondents. This sounds both broad-based and up-to-date, although assessments remain part of the calculation for 24 months, with their weight decreasing on a logarithmic scale.

How disinterested are the respondents? Scores given by respondents to their home centre are not counted, which helps. But that may not necessarily prevent efforts, concerted or otherwise, to tip the scales in favour of one or other financial jurisdiction.

In the past, I have been directly solicited by more than one financial promotion agency (our client Luxembourg for Finance not among them) hoping that in my capacity as a journalist I would provide a flattering assessment of their respective financial centres.

A pinch of salt?

But probably a greater question mark over the scientific rigour of the assessments is that, by definition, the respondents are reporting on up to five financial centres that are not where they currently work and on which they are presumably less expert. There’s also the question of turnover among respondents – whether changes in the indices simply reflect that different people are responding.

Does this mean that Luxembourg’s disappointing results in GFCI 29 and GGFI 7 should be taken with at least a pinch of salt? Certainly – a lot more and harder evidence is needed before one can conclude the country is losing competitiveness as a hub for green finance or overall as a financial centre.

It’s probably a moment to suggest that industry members and policymakers in the grand duchy should perhaps be less occupied with international comparisons and rankings, many of which are based on methodology with significantly less commitment to scientific rigour than Z/Yen’s. Often such exercises are best seen as a tool to prompt reassessment of common assumptions and challenge existing models rather than to ring alarm bells.

So do this year’s downgrades matter? Unfortunately, yes.

The GFCI rankings have become such a widely followed measure of competitiveness, and the GGFI is fast getting there, that every six months their results are bound to cast some influence on decision-makers and others, including potential recruits for the country’s financial institutions, especially among those who know Luxembourg less well. One can only hope that starting later this year, the pendulum starts to swing back.