Should you regard cryptocurrencies as an investment opportunity? That’s a very big question with very different and conflicting answers…and many questions implied.

Are cryptocurrencies the future of currency? Will they challenge the stability of national or global financial systems? Can we expect banks to make cryptocurrency services such as wallets or trading available to retail customers any time soon?

So we asked three finance experts spanning the crypto divide – a banker, a lawyer and a fintech pioneer – for their cryptocurrency predictions and analysis. If you want to know what they expect for the future of this fast-growing and ever-confusing market, read on…

Is the rise in the price of Bitcoin (BTC) and other cryptocurrencies in recent years based on anything more fundamental than the ‘Greater Fool’ theory?

The Greater Fool Theory posits that regardless of whether or not assets are overvalued, they can nevertheless be profitable if the seller can find a ‘greater fool’ willing to pay a higher price.

Investors subscribing to this approach buy potentially overpriced securities while ignoring valuations, earnings reports and any other relevant data – and therefore have no real regard for the fundamental value of those assets.

However, while the theory could contribute to some of the rise in cryptocurrency prices, all three of our interviewees reject the notion that it’s the main driver behind their rapid growth.

Daniele Antonucci, a banker and economist, notes a range of approaches that attempt to value fairly all cryptocurrencies – for example, attempting to estimate their addressable markets and comparing that evaluation to their current market capitalisation.

Another option is to view cryptocurrencies as a network that increases in value as more users are added. And some theories even take into account cryptocurrencies’ cost of production and scarcity, as well as the size of the market they support and their velocity as they move through such markets.

While these approaches have both merits and drawbacks, Antonucci warns that they highlight the commonalities between cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and commodities and currencies – more than with cash-flow-producing instruments such as equities and bonds.

Valuation frameworks for commodities and currencies, he says, tend to be less precise, while traditional discounted cash-flow analysis applies more to equities, and interest and credit models to bonds.

Similarly, Nasir Zubairi, who has worked for more than two decades in financial services and has been immersed in the fintech sector since 2011, draws comparisons to the price of gold. Like gold – of which some 40% of the world’s stock is in bullion, coins and central bank vaults (i.e. being held for its value) – the price of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies is based on supply and demand.

Although Zubairi still has not come across what he would call a robust pricing model for Bitcoin, “demand,” he says, “is clearly there.”

So, what does that mean? Will demand fall off? Zubairi doesn’t think so, at least not in the near-term. He does believe that price volatility should stabilise, though, as the distribution of holdings increases and the power diminishes of the various ‘whales’ in the market to manipulate prices.

Does the slump in price of Bitcoin represent temporary volatility or a long-term effect of government attempts to control or suppress the market, as in China?

Although Jean-Louis Schiltz – a lawyer whose areas of practice include fintech, and former Luxembourg government minister – agrees that sometimes fluctuating cryptocurrency prices correlate to countries’ political announcements or decisions, there’s no identifiable price trend relative to governments’ efforts to control or suppress the market

Zubairi sees no nuance here: “I believe the slump in Bitcoin value is temporary.” In fact, he says that the suppression of (crypto) mining and other activities in China, for example, should actually lead to a more open and accessible market for bitcoin mining by producing more competition.

He sees continued strength in the demand drivers for BTC and other cryptocurrencies, while traditional funds and institutional market participants are launching crypto funds. “Plus,” he emphasises, “banks are increasingly developing and launching crypto services to support investors, and there are strong indications that corporates are looking at BTC in cash management.”

Quintet’s Antonucci, on the other hand, regards Bitcoin’s unpredictability as a feature of its ‘nature’: potential government meddling aside, “the volatility of Bitcoin is quite high, much higher than that of other risk assets. Its price can also vary widely from period to period in comparison to such assets.”

Antonucci argues that few assets are as volatile “apart from oil and other commodities at times… and even then, only for relatively short periods. While precious metals and major currencies tend to be quite volatile too, they are still much less so than Bitcoin. What’s more, Bitcoin’s correlation with the S&P 500, which is relatively unstable, has increased significantly over the past few risk-on episodes.”

Antonucci concludes that, as a partly speculative digital asset, cryptocurrency prices can be impacted by regulatory changes – regardless of whether there are government attempts to control or suppress the market.

While he says this can also apply to other traded assets, Antonucci warns that cryptocurrencies may face unique regulatory challenges in the future, which could fuel further volatility.

An element of cryptocurrencies’ appeal is anonymity and not being subject to government regulation and oversight. Can they survive being subject to AML and other oversight by regulators?

All our interviewees agree that cryptocurrencies must be subject to more regulation and oversight as the market continues to grow. They also say more oversight in this case won’t deter investors, nor will it take cryptocurrencies down – at least, not the ‘good ones.’

As Schiltz points out, crypto exchanges already are subject to regulatory oversight. In the EU, for instance, they must comply with AML rules, which means there is little room for absolute anonymity. “Moreover,” he says, “cryptocurrency transfers are mostly traceable, which enables regulators to ‘follow the money.’”

The notion absolute anonymity is already being challenged – and has not put a brake on development. As Schiltz notes, it’s more down to the relevant actors implementing technical solutions that already exist.

Furthermore, says Antonucci, the market must accept that the same features of cryptocurrencies that might make them competitive with alternative investments – particularly anonymity – are also likely to continue to attract increased government scrutiny.

Zubairi adds that the legitimate market must – and generally does – accept oversight as necessary to combat money laundering and international crime. While small transaction sizes can remain anonymous, for larger amounts – crypto or cash alike – a level of traceability and oversight on the source of funds is required.

In fact, given their ongoing growth in popularity Antonucci expects cryptocurrencies will likely contend with even greater regulation. He believes central banks may well adopt the same or an alternative technology which they can throw their weight behind to launch an ‘official’ digital currency.

According to Zubairi, it adds up to a simple conclusion: cryptocurrencies can and will be able to survive being brought under increased regulatory scrutiny.

Will central bank digital currencies sap demand for private cryptocurrencies?

For Zubairi, it’s important to note that central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) differ from cryptocurrencies: “CBDCs, as a means of exchange, tackle a different problem for the international financial markets and central banks. On the other hand, cryptocurrencies are more similar to investment assets, such as stocks, commodities or bonds.”

That distinction is why he thinks demand for private cryptocurrencies will not dwindle.

Although Antonucci believes that investment in cryptocurrencies could take a hit, he also acknowledges the likelihood that they remain popular as speculative assets, while central bank digital currencies could serve as ‘money.’

“A central-bank digital currency could have all of the properties of cash that Bitcoin does not,” explains Antonucci, “providing a widely accepted means of payment, with a stable price and a store of value.”

His view: it will present a choice and a trade-off between the two digital currency types: a central bank digital currency would likely have to be permissioned, unlike a cryptocurrency that is permissionless.

The key contrast between the two is that within a permissionless blockchain anyone can opt in to validate transactions (by mining) within the network – a slow and energy-intensive process. Meanwhile, a permissioned blockchain may be able to process payments more quickly, allowing the network to increase speed and capacity, but at the cost of sacrificing features such as independence and flexibility. The question is whether the market will evolve a clear preference for one over the other.

We want your cryptocurrency prediction: will they threaten the stability of national or global financial systems?

All our interviewees agree: There is no threat.

Schiltz: “Even if cryptocurrencies became a threat in the future, the ECB and other regulatory bodies would undoubtedly remedy that situation.”

Antonucci: Despite that Bitcoin, like any other traded asset, could create instability, it would presumably be regulated to mitigate that risk. “Even if cryptocurrencies somehow led to instability – for instance as a result of unchecked speculative behaviour or competition with central bank money and transparency issues – there are solutions available to put effective regulation in place, as already exists for other traded markets.”

Zubairi: The circulation and use of BTC, as with all the other cryptocurrencies, currently represents just a drop in a much larger ocean when compared to the traditional capital markets.

Should financial institutions make cryptocurrency services such as wallets, trading and investment available to retail customers? What consumer protection measures would be appropriate, or feasible?

“Cryptocurrencies are part of the evolution of financial services,” says Zubairi, “and banks and other financial institutions should therefore evolve in line with their customers’ needs.”

Schiltz agrees that if the demand is there, financial institutions should make crypto services available to their retail customers.

Both interviewees also note that offering crypto-related services would help financial institutions stay competitive (and in control of their clients’ assets).

“Think about it,” warns Schiltz. “If retail clients have to turn to other service providers for their crypto needs, there is a risk that those competitors could also start offering the same traditional banking services. After all, most of the crypto service providers can qualify as financial service providers easily enough, and the same consumer protection rules that govern the financial sector can then apply to their cryptocurrency services as well.”

Providing such services would also help protect customers, says Zubairi. A bank that offers crypto-related products must adhere to strict regulatory requirements. But if banks don’t offer these services, retail customers could resort to accessing crypto through less legitimate sources or businesses with weaker safeguards.

On the other hand, as the resident banker on this panel, Antonucci takes a far more pragmatic view: “There wouldn’t be a one-size-fits-all formula. There’s a laundry list of factors at both the institutional and end-customer level that would come into play for any financial institution wanting to offer crypto services to retail investors.”

In order to offer such services, he continues, consumer protection agencies would have to treat cryptocurrencies as speculative investments, not money, which would present its own set of obstacles.

For a financial institution to accept a cryptocurrency as an ‘alternative’ means of exchange, he explains, would mean the bank is capable of taking a closer look at the very features that currently make the crypto market so attractive to many investors, such as its anonymity. Who knows if the teams behind these cryptocurrencies would agree.

“Plus, those are the very features that would undoubtedly attract additional government scrutiny and regulation if financial institutions were to offer crypto services to retail investors in the first place,” he concludes.

Ultimately, Antonucci finds that the volatile price of Bitcoin and most cryptocurrencies is a major issue. For financial institutions to consider offering such products, “volatility would likely need to come down and prices would probably need to become less correlated with those of risk assets.”

Zubairi disagrees. He doesn’t believe new regulation will be required to protect consumers specifically when trading cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. Rather, it will be a question of applying existing regulations correctly.

“Look at Bitcoin and Ethereum, for instance,” he says. “These are two of the most heavily traded assets on any given day in the US markets. In fact, their average daily trading value is higher than that of the big tech stocks such as Tesla, Apple, Alphabet or Amazon.”

“So,” he asks, “how much longer can the crypto market be avoided by financial institutions? After all, volatility drives volume – and higher volume means more fees for banks and brokers.”

— — —

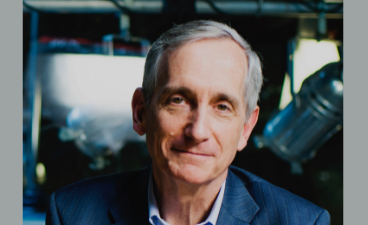

Daniele Antonucci is Chief Economist & Macro Strategist at Quintet Private Bank. In addition to overseeing the firm’s research activities to identify and forecast key global trends shaping the economic and policy outlook, he is also responsible for translating these analyses into investment views on interest rates, currencies and commodities. Before joining Quintet in 2020, Daniele served as Chief Euro Area Economist at Morgan Stanley, and has held positions at Capital Economics, Merrill Lynch, Moody’s KMV and the Confederation of Italian Industry. Based in London, he holds a master’s degree in economics from Duke University, graduated from the Sapienza University of Rome and studied at EHSAL in Brussels. Daniele is a member of the ECB Shadow Council.

Nasir Zubairi is the CEO of The LHoFT Foundation – The Luxembourg House of Financial Technology – Luxembourg’s platform to drive digitisation in financial services. He sits on the IMF’s High Level Advisory Group for Finance and Technology and the OECD’s Blockchain Expert Policy Advisory Board. Nasir has worked in Financial Services for 24 years. He spent 13 years working in the front office within Capital Markets at RBS, ICAP, HSBC and EBS and he has been a Non-Executive Board director at Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB) S.A., the leading Scandinavian Bank. He is signatory for several patents related to FX electronic trading that revolutionised liquidity and market access. Nasir has been immersed in the fintech and startup sector since 2011. As an entrepreneur, Nasir has built multiple fintech businesses, both B2B and B2C, focused on lending, banking and payments. He has a BSc from the London School of Economics and is a Sloan Fellow from London Business School.

Jean-Louis Schiltz is the Senior partner at SCHILTZ & SCHILTZ specialising in Corporate, Regulatory & Compliance and Financial Services & fintech areas of practice. An honorary professor at the University of Luxembourg and fintech pioneer in the Grand Duchy, Jean-Louis is a regular speaker at conferences with a focus on innovation and technology law. From 2004 to 2009, he served as Cabinet Minister in Luxembourg – his portfolio included media, telecommunications, technology, international development and defence. Jean-Louis holds a post-graduate degree (DEA) in business law from the University of Paris I, Panthéon-Sorbonne.