How much do you know about investing in the recycling sector? Not as much as you may think, we’ll bet.

So we spoke to Kai Curry-Lindahl, a fund manager and recycling expert at Active Niche Funds, who explained that the industry is in a major phase of innovation and a prime target for investment — if you know what you are doing.

In this Q&A with VitalBriefing, Kai provides insights on the current state of the market, its growth drivers, and what potential investors should know before they leap.

Let’s start with what might seem a simple question: How would you describe investor interest in recycling?

Recycling is a topic that naturally draws interest from investors and the public alike because it’s part of everyday life. You can’t help but see it around you – on packaging labels and product materials, and in how companies talk about their environmental impact. Teaching the importance of recycling has become part of school curriculums.

It’s visible and relatable, and people are curious about how it works. That familiarity creates a strong foundation for deeper engagement. It is an important element that contributes to a wider, society-wide understanding of the importance of recycling, which does stimulate investor interest.

From an investment standpoint, the connection to recycling is direct – not just a feel-good concept but a structural megatrend. Demand for recycled content is growing and supply chains are being reshaped to include more circular inputs, while regulatory pressure and corporate commitments are driving volumes higher. Investors are quick to pay attention to opportunities in the infrastructure behind this – a rare case where what people see all around them is aligned with a long-term, scalable investment opportunity.

Examples of companies adapting their supply chains are legion, especially under pressure from consumer demand, from beverage companies focused on boosting recycling of plastic bottles and European car manufacturers using recycled rather than virgin steel to shipping companies using recyclable packaging.

Is there confusion between recycling and the circular economy? Does the difference between the two impact investment?

There’s definitely confusion among investors — even fund managers. Recycling and the circular economy are often used interchangeably, but they are fundamentally different concepts.

Recycling is about giving new life to waste, an industrial process that includes collecting, sorting, processing and converting scrap material into new products. It’s tangible, measurable and already operating at scale. The circular economy includes designing goods to be more easily recycled, but it also involves durability, reusability and reducing waste through smarter design. However, many products are still made using virgin materials, so they don’t necessarily reduce the need for new resource extraction.

Plus, there’s a whole other layer of complexity. Some circular design choices, like making products more durable or reusable, can actually make them harder to recycle at the end of life. So while circular economy principles aim to reduce waste overall, they are not always aligned with recycling. That’s why evaluating circular economy companies requires close examination of the full lifecycle and business model to understand whether they are actually contributing to sustainability in a meaningful way.

It is critical to understand what drives the profit and loss of companies in a fund, hence the performance of the fund itself. How the syntax of a thematic investment fund is defined is really important. A key distinction is whether a company must contribute to a theme, benefit from it, or both.

Many managers fail to understand this difference, or include both to simplify their portfolio construction, but this can dilute the investor’s exposure to the actual investment thesis. An investor looking to invest in a specific thematic fund must ensure that portfolio companies benefit from the theme, rather than contribute to it.

An example: Coca-Cola is often included in circular economy funds, since it is increasingly buying more recycled plastic bottles and aluminium cans. However, the P&L of Coca-Cola is not driven by this element of the business or by its contribution to the circular economy – its revenue, profit and share price depend primarily on the volume of drinks sold, not bottle recycling.

This creates a major disconnect. An investor buys into a compelling theme, expecting company performance and therefore fund returns to be linked to that trend. But if companies’ business models aren’t actually driven by the theme, the link is lost. True impact-driven investors should pay close attention to a high purity level in benefiting from the underlying theme.

What technological developments are driving the recycling market?

Ten or 15 years ago there was very little R&D in recycling, but that’s changed dramatically. Recycling’s emergence as a megatrend has boosted demand, scaling up of infrastructure and improved margins, which has attracted capital – bringing innovation, especially in the last few years.

Sorting is a great example. For years, recycling relied on households to separate materials, but high contamination and inefficiencies meant facilities had to sort waste manually, which was costly and slow. Now optical sensors, robotics and AI are automating sorting with far greater accuracy. As the technology scales up, the need for consumers to sort at home is starting to decline because machines are simply better at it. For investors in the sector like us, investing in companies that develop sorting solutions is a great opportunity.

Another area of rapid progress is plastics, off which currently only about 9% is recycled. Traditional mechanical recycling requires very clean, uniform plastic streams, but most products are made from multiple types of polymer – with a simple water bottle, the cap, bottle and label are made of different plastics that machines struggle to separate, losing quality in each cycle. At best, plastic gets two or three lives, progressively downcycled into lower-grade uses like plastic bags before ending up in landfill.

Now companies are developing chemical recycling technologies that could enable processing of mixed plastics together, breaking them down to their molecular base and rebuilding them into high-quality plastic – closing the loop. We’re not fully there yet, but the momentum is real. Innovation is rapid across collection systems, reuse platforms, recycled content tracking and advanced materials, and we believe it’s still early in that innovation curve.

How is legislation pushing growth of recycling? Can industry capabilities such as municipal waste collection and sorting keep pace?

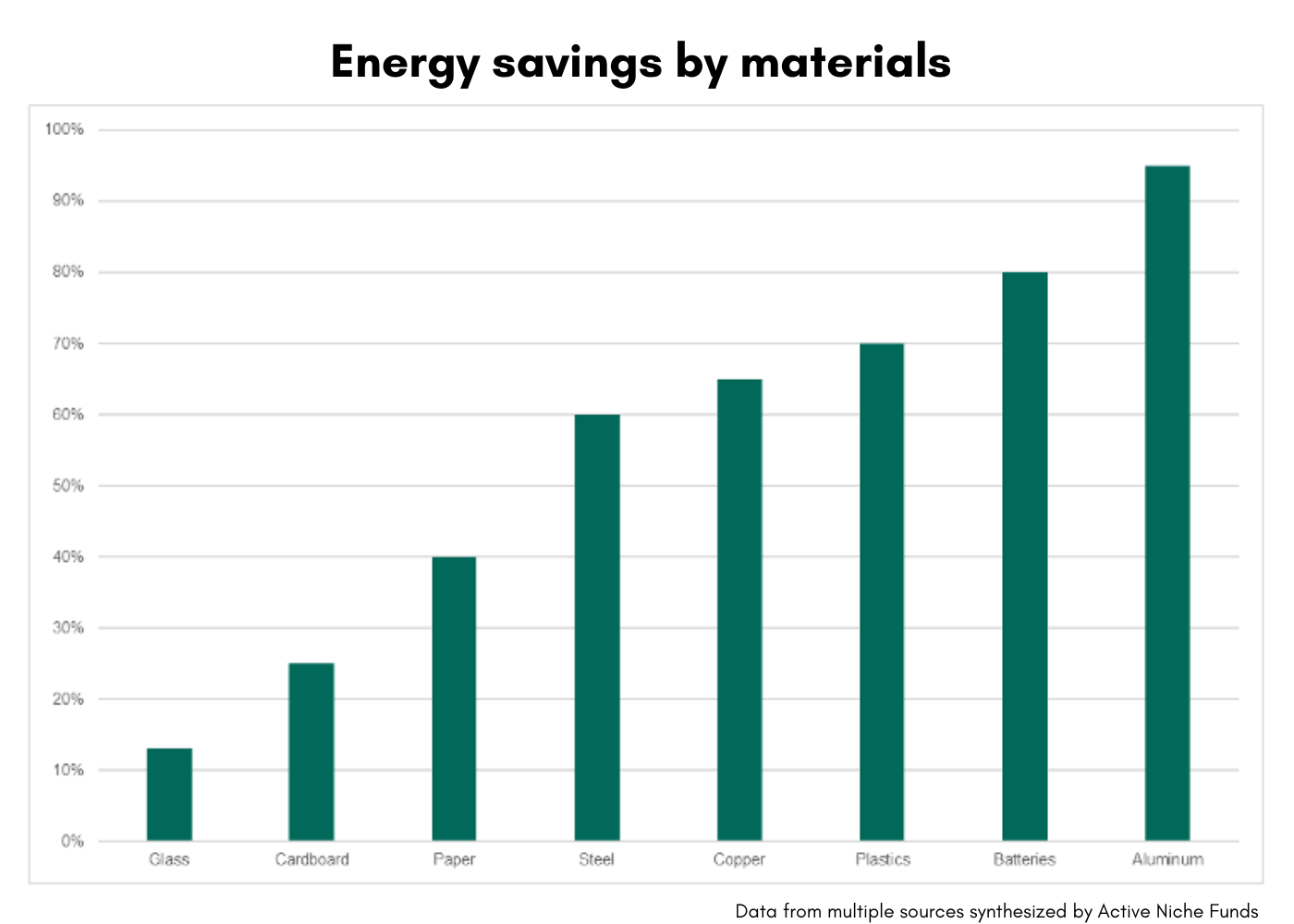

A wave of legislation worldwide is seeking to accelerate recycling, not only reducing physical waste but cutting carbon emissions, as can be seen in the graph below. It diverts material from landfill, where decomposition generates methane, and manufacturing a product from recycled material typically uses significantly less energy than producing the same item from virgin resources. So the policy shift makes sense.

Recent legislation has created real momentum. The EU’s proposed Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) sets binding targets for recycled content in plastic packaging — 30% by 2030 for certain formats. France’s Anti-Waste and Circular Economy Law (AGEC) is also pushing companies to improve product design, labelling, and recyclability.

U.S. states including California, Washington, and Oregon have passed Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) legislation shifting the cost of recycling from taxpayers to producers. These policies support demand for recycled materials, improve collection systems and raise the bar for producers.

However, we view legislation as a tailwind rather than a requirement. The best recycling businesses already operate with strong fundamentals and scalable models, and while regulation helps, they don’t depend on it to survive. As a fund, we avoid segments that can’t function without subsidies, focusing instead on companies that are profitable today and positioned for long-term growth with or without government support.

It should also be noted that regulation is critical at the upstream level, particularly in driving consumer behaviour. Without sorting requirements or incentives, the general public has little motivation beyond the feel-good factor to separate waste streams, without which recyclers would not get the quality feedstock they need.

As for infrastructure, there’s a perception that systems can’t keep pace, but in reality, the challenge is often about scale. Municipalities may struggle to invest in downstream infrastructure simply because volumes are too low. But when recycling is privatised and consolidated, those barriers largely disappear, because recycling at scale is economically viable. It makes more sense to extract value from waste than to pay to landfill it.

To what extent are industrial companies incorporating recycled materials into their supply chains?

We’re seeing industrial companies incorporate recycled materials into their supply chains at an accelerating pace, one of the key drivers of growth in the market, for two main reasons. First is consumer demand. More people are paying attention to what their products are made from, and recycled content is increasingly a selling point. If quality and design are the same, consumers are likely to choose the more sustainable option. That creates a competitive advantage for brands that integrate recycled materials, and many are actively building that into their sourcing strategies.

Secondly, companies are under pressure to meet sustainability goals, particularly on carbon emissions, and one of the most effective ways to reduce Scope 3 emissions is by using recycled inputs. In the steel industry, US electric arc furnace steel producers such as Nucor and Commercial Metals Company, which use scrap as their primary feedstock, have consistently outperformed traditional blast furnace operators not just in emissions but in economics as well, producing the same quality of steel using up to 60% less energy. That’s a compelling proposition for customers trying to reduce supply chain emissions.

In consumer goods, groups such as Unilever and Nestlé are incorporating more recycled plastics into their packaging, in response to both consumer expectations and legislation that mandate minimum recycled content. Recycled materials are becoming a core part of industrial and commercial supply chains.

That shift is putting pressure on the supply side. High-quality recycled inputs such as food-grade plastics or low-impurity scrap metal are increasingly in demand, and sometimes trade at a premium to virgin material, a big change from a decade ago. For companies that can secure reliable feedstock or have access to processing capacity, this is becoming a strategic advantage, where we see significant investment opportunity.

What waste products offer the greatest economic potential for recycling?

Metals offer some of the greatest economic potential in recycling – most can be recycled indefinitely without any loss in quality. The end product is structurally identical to one made from virgin material, which is not the case for other materials such as plastic or paper.

But the real advantage lies in energy savings and the cost structure. Producing metal from scrap requires significantly less energy, not just during the melting phase but across the entire value chain – replacing mining, refining and transport with local collection and sorting, resulting in lower operating costs, fewer authorisation hurdles and shorter supply chains.

Recycling aluminium uses up to 95% less energy than producing it from bauxite, and the same is broadly true for steel, copper and other industrial metals. Add the fact that metals hold their value well and are widely traded, and it’s a material class that’s not only sustainable but economically compelling to recycle at scale.

What statistics are available on the growth of the recycling market in Europe and worldwide, over (if possible) one, five, 10 and 20 years, in terms of value and if possible volumes, with a breakdown for different types of material?

This question is more difficult to answer properly as there is no unified/centralised source of data for this.

Different countries and associations that report this information use their own ways of calculating. So it becomes hard to compare apples to apples.

That said, I’ve compiled some relevant data from multiple sources below that help give some context:

| Material Type | Market Value (USD Billion) | CAGR (2025–2030) | Notes |

| Metals | 2020: $222.08bn 2030: $368.7bn | ~5.2% | Driven by energy savings and demand in construction and automotive sectors. |

| Plastics | 2023: $46.6bn 2033: $68.2bn | 3.88% | Growth fueled by consumer demand and regulatory pressures. |

| Textiles | 2023: $6.89bn 2030: $10.57bn | 6.3% | Increased focus on sustainable fashion and waste reduction. |

| Chemical Recycling | 2025: $8.90bn 2030: $14.38bn | 10.05% | Addresses hard-to-recycle plastics through advanced technologies. |

| Battery Materials | 2030: $6.0bn (est.) | N/A | Recovery of lithium, cobalt, and nickel from end-of-life batteries. |

— — —

Kai Curry-Lindahl is a fund manager at Active Niche Funds, where he manages the Active Recycling Fund, a long-only global equity fund focused on the recycling industry. He brings deep expertise in fundamental equity analysis, long-term thematic investing, and building high-conviction portfolios. In addition to his portfolio management responsibilities, Kai leads Active Niche Funds’ ESG analysis, integrating environmental and sustainability considerations into the investment process. He previously co-managed the Sparrow Hawk Fund at Fidelity Capital Management and worked at Credit Suisse as a financial advisor. He holds an MBA from Cornell University and a Master’s degree in Biology from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington — a combination that uniquely positions him to analyse both the financial and environmental dimensions of the recycling sector.