Key takeaways

- ESG and sustainability generally are becoming top priorities for organisations of all sizes and in all sectors

- Naming a single individual or team to lead and coordinate ESG efforts can make sense especially for larger organisations

- There must be buy-in, commitment and communication from an organisation’s C-Suite for its ESG activities to be successful (and more than a ‘greenwashing’ equivalent)

- ESG frameworks such as B-Corporation can facilitate the kind of internal culture change that ensures success

Head of ESG, (senior) ESG officer, chief sustainability officer…increasingly, positions like these are being created to fulfil organisations’ ESG commitments and goals. But with this trend come big questions. For example, is it effective to place corporate sustainability-related responsibilities on a single individual? Is there a risk that some businesses use the appointment of an ESG-dedicated employee as a greenwashing tool?

To help us explore and understand this trend – and whether or not you actually need somebody to head your ESG operations – we’ve asked two experts to provide much needed insights: Andy Schmidt, co-founder and Chief Community Officer at Seismic, a sustainability consultancy dedicated to helping businesses become impactful forces for good, and Oksana Sisterhenn, senior manager at Avantage Reply Luxembourg, a specialised management consultancy delivering change initiatives in the financial services industry.

What factors have prompted the emergence of the role within large corporations of (chief) ESG officer?

The growing number of (chief) ESG and sustainability officers correlates with the fact that these are issues that are now in the mainstream — no longer is it an uphill battle to get ESG on the agenda of executive leadership teams and boards.

With consumer demand and regulatory pressures piling on, corporate responsibility is fast-becoming a serious concern, not simply window dressing thrown over to and managed by marketing and communications departments.

“Due to the rapidly evolving expectations of stakeholders, from clients to consumers, investors, talent and regulators, ESG is now a top priority for exec teams in corporations large and small, driving them to recruit Chief Sustainability Officers or ESG Directors,” says Schmidt.

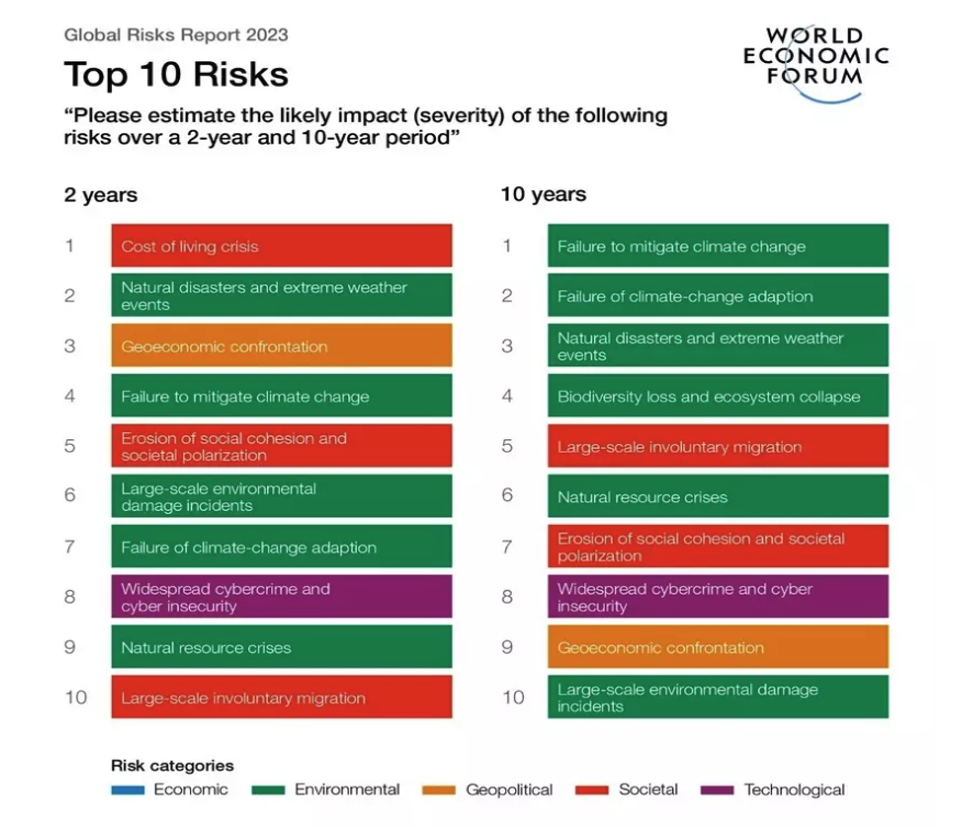

For Schmidt, the proof is spreading around the world: “Take a look at the top risks identified in a recent report from the World Economic Forum – they are all in some way ESG-related. These risks will have an enormous impact on business in both the near and longer-term.”

Meanwhile, as Sisterhenn points out, “there is a huge increase in regulatory requirements especially around disclosures. These new disclosures around sustainability and ESG require collection of new data and development of new reports.”

Similarly, says Sisterhenn, there is also clear evidence that market demand for sustainable or ESG products is substantially increasing, which has led companies and financial service providers to begin adapting their orientation and business strategy accordingly.

What specific characteristics of a company might cause it to need a chief ESG officer? Is it a matter of size?

On one hand, argues Schmidt, a connection between the size of a company and its ‘need’ for somebody (or multiple people) to spearhead ESG efforts makes obvious sense. After all, as companies grow in size, they grow in complexity, thus impacting more stakeholders.

However, size is not the only factor – nor is it the main one. Companies operating in specific industries or sectors may find greater expectation to have a Chief ESG Officer. “Highly regulated industries such as financial services or industries with significant social or environmental impacts would, for example, benefit significantly from a dedicated leader to ensure the business is taking ESG seriously – and to demonstrate this to the public,” says Schmidt.

According to Sisterhenn, ultimately it depends on how each organisation decides to structure its governance process to cover ESG risks. “Generally,” she says, “what we see on the market is that organisations create specific, dedicated ESG roles across various functions to jointly cover the governance of the ESG risks.”

As ESG becomes a larger priority, the need for a lead ESG officer makes more sense.

To what extent is the appointment of an executive whose primary concern is sustainability important in focusing the attention of the business as a whole on environmental, social and governance priorities?

For Sisterhenn, this trend actually may not represent a net positive. She believes that organisations that appoint an executive to spearhead ESG in fact run the risk of de-prioritising their efforts.

When an individual is expected to manage all things ESG, Sisterhenn says that the rest of an organisation’s leadership in many cases react by avoiding any related responsibility. Moreover, having a single executive in charge of ESG initiatives can lead to a narrow-minded view on the relevant issues within the organisation, she warns.

Rather, the ESG journey should be seen as a collective responsibility of an organisation that involves participation across its entire footprint.

Schmidt, on the other hand, argues for the need for organisational oversight. Therefore, having a person or group within an organisation to drive ESG performance can be crucial. It’s up to the C-Suite, he says, to ensure that all employees understand and support the commitment to ESG.

According to Schmidt, the need for a specific executive to focus on ESG depends on a variety of factors including company size, sector/industry and relevant stakeholders. In cases where a Chief of ESG is not deemed necessary, there are mechanisms that can be integrated to drive the change required, or which can be used to complement the work of whoever is in charge of ESG.

Ultimately, though, says Schmidt, there needs to be an individual or group within the organisation at the helm of ESG oversight. For large organisations, appointing a dedicated executive in charge of ESG performance often makes sense, while such a position may not be necessary for small and medium-sized companies. Instead, working groups or steering committees can be established to drive purpose, performance and progress.

Schmidt advises that companies feature an important element: implementation of an ESG framework such as B Corporation. Such a move will simplify developing and integrating ESG strategies, breaking them up to ensure they’re manageable. For companies that lack an ESG-committed executive, integrating an ESG task force, committee, steering group, department or team goes a long way to ensuring adherence to the framework.

How does the position of chief ESG officer overlap (or even conflict) with existing corporate risk and compliance posts and structures?

Both experts agree that an ESG officer’s role should not conflict or overlap with corporate risk and compliance structures.

Says Sisterhenn: “The ESG officer is there to support existing risk and compliance posts and to enhance the coordination between various departments of a firm.”

Schmidt advises against viewing ESG through the lens of risk and compliance as it will prevent organisations from leveraging the biggest business opportunity of this generation: “Businesses that understand, manage, improve and effectively communicate their impact on people and the planet are the businesses that are going to have the greatest growth opportunities in the years and decades ahead.”

So, although Schmidt believes this undeniable trend shows there is vast room for collaborations between ESG, risk and compliance, it also indicates that “having a Chief ESG Officer ensures that investments in ESG are creating the most value for the company by enabling growth, talent attraction and retention, alongside regulatory compliance and risk management.”

Sisterhenn argues that another important factor to consider is that the risk relevant to ESG-related regulations tends to focus on the ‘E’. As a result, she points out, risk and compliance will focus primarily on those risks specifically. The ESG officer’s remit, on the other hand, covers all three elements equally: the E, S and G.

One example Sisterhenn gives of the ESG officer supporting (rather than overlapping with) risk and compliance, related to the fact that ESG data is often located across multiple corporate functions. In these cases, it’s the ESG officer’s job to support risk and compliance functions in the identification and measurement of relevant data and its sources.

Might the appointment of ESG officers lead to internal confusion and add to bureaucracy? How can their roles dovetail rather than clash with those of other corporate officers?

“Of course,” says Schmidt, “there is always that potential for confusion or increased bureaucracy with the creation of any function.”

However, he believes the position of Chief ESG Officer is a great example of how holistic functions set up effectively can break down silos and enable collaboration.

To that end, Sisterhenn stresses that the appointment of any level of ESG officer must align with an organisation’s business strategy: “The clear definition of the governance around the management of the ESG risk is key to avoid any confusion in roles and responsibilities between the ESG officer and other structures.”

Again, Schmidt emphasises the advantages of B-Corp-style frameworks, which help all stakeholders across a company to better understand social and environmental performance and provide a blueprint for bringing together a cross-functional team. It can even be used as a rallying cry that galvanises staff, offering an engaging activity that all teams can contribute to.

Is there a danger of companies using such titles as a statement of ESG virtue rather than a post with a meaningful role in decision-making (i.e. greenwashing)? Is there also a risk of executive title bloat?

Yes, both experts agree, that these are significant risks. Sisterhenn worries that the use of such titles can often be seen – and used – as a tick-the-box exercise.

Meanwhile, Schmidt warns that if there isn’t the belief and commitment within an organisation that sustainability is a top-five priority, then it runs the risk of executive title bloat.

Schmidt points out, “With regard to the symbolic nature of appointing a Chief of ESG, a part of the motivation of hiring someone to fill the position is often to demonstrate to both internal and external stakeholders that sustainability is taken seriously by the business. Unfortunately a risk arises when a Chief of ESG is appointed only for the optics and the work to understand and improve actual impact on people and planet is not actually being done.”

This is why both experts strongly advise organisations ensure the ambitions for appointing a Chief ESG Officer align with wider business strategies and structures.

— — —

Andy Schmidt is an impact advisor. His belief that business can and should be a force for good in the world led him to co-found Seismic, through which he supports the growth and development of value-led organisations and helps brands to improve their social and environmental performance.

Oksana Sisterhenn is leader of Avantage Reply’s Luxembourg ESG and Climate Risk practice for financial services. She is an expert in banking climate risk, model risk management frameworks, stress testing, and credit, liquidity and operational risk management.