It took massive public-sector bailouts financed by unprecedented levels of borrowing to reverse the global financial crisis of 2008-09 brought on by rash lending and investment policies of banks in the United States and elsewhere. With the world on the brink of a coronavirus-triggered recession, how is it different this time?

“In 2008, the banks were to blame for the crisis, but the real economy was not in crisis,” CSSF CEO Claude Marx observed recently. “Now we are in the reverse situation, where a health crisis is causing an economic crisis, and…the banks are part of the solution.”

In fact, the abrupt cutback of bank lending in 2008 and 2009 contributed to the plummet of most countries’ economies into recession.

However, Marx notes, the confidence enjoyed by the banking sector is a critical aspect of governments’ response to the current coronavirus pandemic. One reason: new rules designed to ensure that institutions are substantially better capitalised than 12 years ago, as well as guarantee schemes expanded to protect retail deposits.

Imprudent parents

Increased transparency affecting both regulators and investors, as well as tools such as stress tests, have been established to prevent both a ‘business-as-usual’ mentality and disregard of the lessons of the century’s first decade.

In the grand duchy in particular, cautious business practices are a well-engrained habit already. For that, we can credit the two Luxembourg institutions that required state rescue: Dexia BIL and Fortis Banque Luxembourg, both brought down by the imprudence of their parents abroad.

For the most part, privately-owned commercial banks have played the key role in channelling government funding into loans and guarantees to preserve businesses and jobs.

But Marx acknowledges that the risk of a recession brought on by the coronavirus cannot be ruled out altogether.

If the economic shutdown prompts widespread bankruptcies and defaults on the share of government-backed loans where the risk is retained by commercial institutions, as well as on previous lending, we may be headed again for trouble.

Because of the banks’ capital strength, and in several cases deep-pocketed shareholders, the risk of a coronavirus-based recession affecting Luxembourg is lower than in most other countries.

But policymakers worldwide must consider seriously the risk as the confidence of a rapid rebound that was widespread just months ago — remember the famous V-shaped recession and recovery? — has begun to fade.

Today, economists are illustrating the recovery with hockey stick charts more like Nike’s trademark swoosh logo.

Risk of losses

Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell has argued that US economic activity could contract temporarily by as much as 30% and that a full-scale recovery may be delayed until the end of 2021. He says it depends on people regaining confidence that their risk of illness is low, which in turn may rest on the widespread availability of a Covid-19 vaccine.

He expects unemployment to continue to climb for at least another couple of months before a rebound begins in the second half of this year.

Already, the Fed has warned in its semi-annual report on financial stability that US banks are at risk of material losses that could strain even their post-financial crisis capital and liquidity buffers, as well as the billions of dollars they have set aside in provisions for potential non-performing loans.

Any renewal of volatility in financial markets could create additional financial stress if asset prices fall, it adds.

There is also concern in France’s banking sector about the longer-term implications of the government’s credit guarantees. Industry members warn that a significant number of companies taking government-backed loans could be heading for a debt crunch over the next next years — perhaps as early as this summer — given that their profitability is likely to remain depressed for some lime.

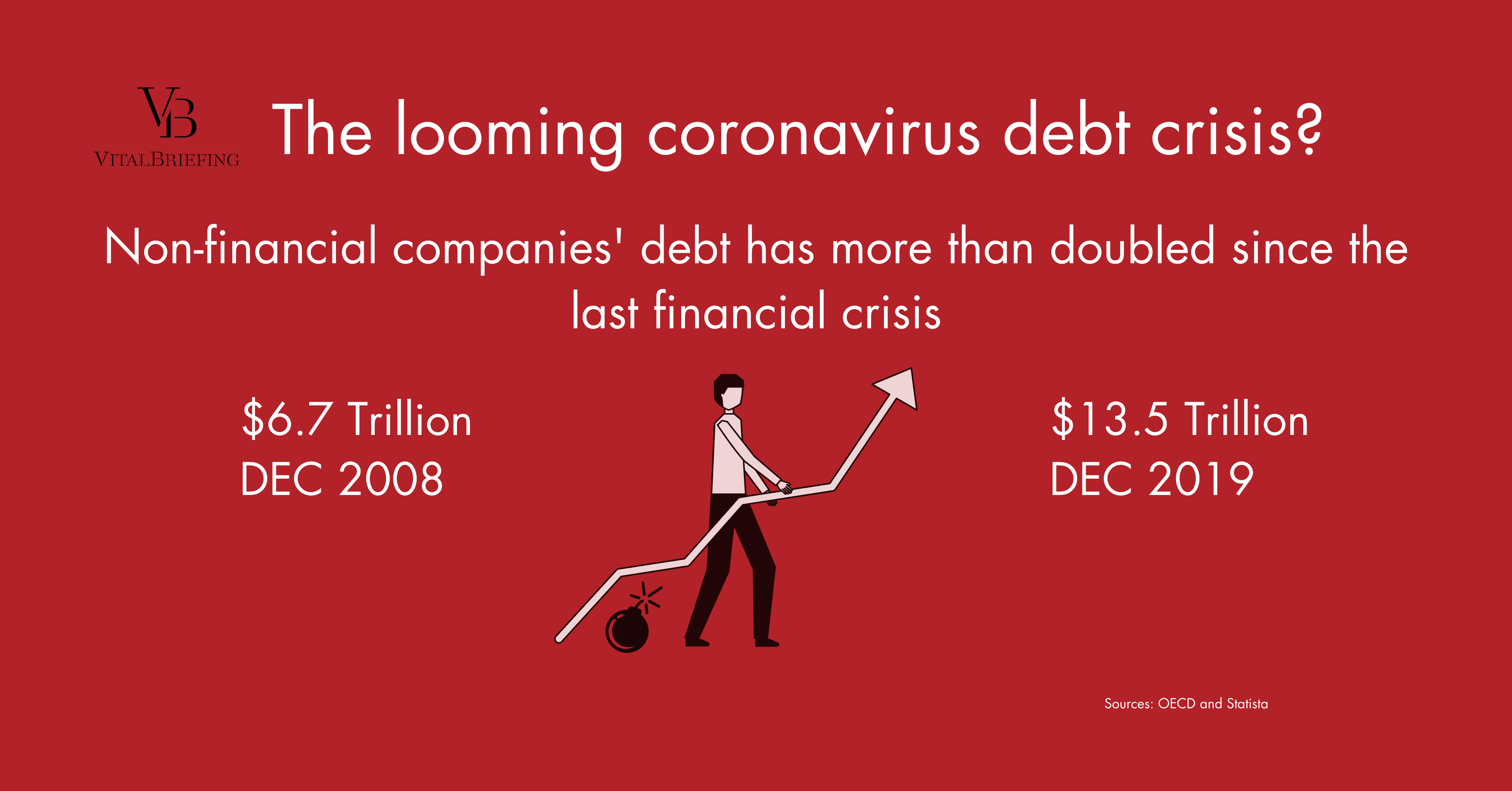

Encouraged by the European Central Bank’s ultra-low interest rates, companies have been loading up on debt in the form of bank loans and bond issues for years.

“The risk is that by putting French companies that were already not in good health on life support, we could be adding a financial crisis to today’s consumption crisis, perhaps in a year, when companies are no longer able to refinance themselves and banks may be closing the credit taps,” worries Pierre-Arnoux Mayoly, a partner with law firm McDermott Will & Emery.

Apart from general concern about businesses, especially small ones, and households whose financial equilibrium may have been eroded by loss of income since March, policymakers are closely examining companies in particularly vulnerable sectors, along with those that were already heavily indebted before the pandemic took hold.

Potential problem areas that were already causing concern before the pandemic include highly-leveraged hedge funds disproportionately affected by market volatility and asset price declines.

They also may have contributed to the turbulence by having to sell assets to meet margin calls or reduce portfolio risk. A year ago 14% of US hedge funds accounted for half the industry’s net borrowing.

Leveraged but not covenanted

Red flags are also waving over so-called leveraged loans — lending to companies that were already highly indebted, typically with debt exceeding five times their earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (ebitda).

These include a significant number of private-equity-owned companies burdened with debt from their acquisition cost or from special dividends paid to investors — paid not out of profit but additional borrowing.

Analysts say the two high-profile, private equity-owned US retailers, J. Crew and Neiman Marcus, that have filed for bankruptcy over the last two months were crippled by debt burdens — $1.7 billion and nearly $5 billion respectively — that prevented them investing to meet the challenge of e-commerce and new shopping habits.

The sector’s problems aren’t purely coronavirus-recession-related. Indeed, they have been worsened by the steady erosion over the past seven years of loan conditions imposed by banks, especially for leveraged loans and private equity-backed companies.

This trend has developed over the past decade amid rock-bottom interest rates that prompted lenders to compete for the business of more lucrative but riskier borrowers.

According to Moody’s, syndicated leveraged loan covenant quality set a decade-long low in the fourth quarter of 2019, with the majority of credit agreements permitting, for example, collateral-stripping asset transfers, the retention by owners of excess cash flow of the proceeds of asset sales, and substantial ebitda adjustments.

Easing capital rules to avoid a coronavirus downturn

Meanwhile, central banks and regulators have been accommodating with banks in the interests of keeping loans flowing into the economy, allowing institutions to draw on capital buffers introduced since the global financial crisis and to delay for a year compliance with new Basel III capital standards, measures designed to prevent a repeat of the banking sector’s problems in 2007-09.

The European Parliament is considering legislation that would ease stricter bank leverage ratio requirements due to take effect next year.

In addition to a one-year delay, the European Banking Federation also is backing an existing measure that would allow national regulators to exclude deposits held at the European Central Bank from their balance sheet total for the purposes of calculating the ratio.

Some governments want to go further. France’s finance ministry says the government-guaranteed loans issued by banks should receive the same treatment. There are even calls for the state debt on banks’ books to be excluded from leverage ratio calculations, a measure already temporarily in place in the US.

So while the banking industry may be confident right now that this time it is not the problem but the solution, a little caution is appropriate — the potential of a coronavirus recession is very real.

Neither the Covid-19 pandemic nor its economic consequences are close to being fully played out, and not even the most prescient expert can predict with assurance where all the chips are going to fall — or when.